by Andy

After our first taste of Wilderness Medical Training, I felt a strong desire to desire to learn more, so on bright May morning in 2003, I set out with university friend Dan Kefford to the Churchill Hospital, Oxford to attend Part 2 of Wilderness Medical Training’s ‘Far From Help’ course.

The course built on the foundations laid by Part 1 of ‘Far from Help’ which Nick and I had already attended at the Royal Geographic Society in London. This provided an excellent opportunity to both revise some of the skills that we had learnt then and to acquire some new ones.

We began by reviewing of one of the most important aspects of any medical treatment: taking a good medical history. We also extended what we had learnt in London about quickly evaluating a casualties condition, by working through examples of situations where it might be necessary to rapidly prioritise the treatment of several casualties in a variety of different conditions.

We also covered dealing with venomous bites and stings, although after we were shown a slide showing a man having been swallowed whole by a snake in Africa whilst taking an inebriated slumber down by the river, I couldn’t help feeling that there are some situations where no amount of Wilderness Medical Training is going to be of use.

The day closed with a chance to really get stuck in on the practical front, as we took it in turns to suture a very cooperative slab of pork belly, having first carefully made it comfortable with an local anaesthetic of saline. Needless to say, I personally would be asking for something a little stronger before letting Nick patch me up on the road to Sydney.

A pleasant summer’s evening meant that The Head of The River pub in Oxford itself made for the perfect place to unwind and relax and chat to both to our instructors and our fellow Wilderness Medical Trainees. In common with our first Wilderness Medical Training course in London our time in Oxford provided an excellent chance to mingle with a great bunch of like-minded people, exchange ideas and listen to some fascinating travel stories.

Refreshed and revitalised after being well looked after by Dan’s relatives, with whom we were staying, we made an early start the following morning with some more practical sessions. Although we hope we’re never going to need them, some of the skills we learnt on the course were particularly relevant to our own expedition, for instance learning how to safely remove a casualty from a vehicle.

Being able to administer injections in the field is a very useful skill and opens up a whole range of treatment options which would not otherwise be available. These include the option of administering more powerful and fast-acting pain killers, or giving antibiotics even if the patient was unable to take these orally for any reason.

But any injection carries with it the risk (however small) that the patient might experience an serious adverse reaction, and so before we were let anywhere near a syringe, we spent some time learning about treatment of anaphylactic shock and the essential ingredients in a expedition medic’s ‘shock kit’.

We then got the chance to practice giving each other intramuscular injections, which went well, even if Dan did take Dr Jon Dallomore’s advice that when giving an injection ‘…imagine you’re throwing a dart’, a little too literally at first…

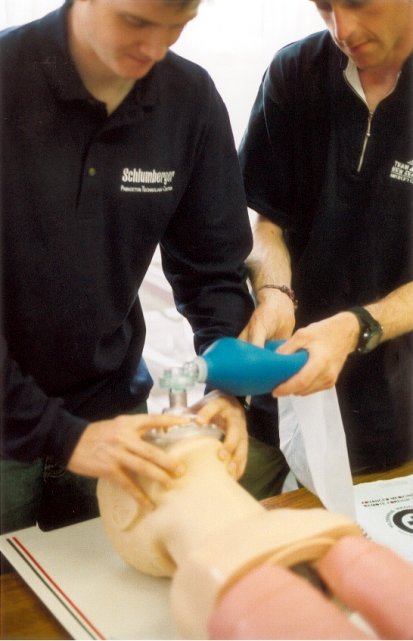

Other advanced skills we practiced included setting up a cannular in order to be able to administer intravenous fluids—another potentially life-saving procedure—which, on the whole, passed with a surprisingly little amount of bloodshed.

All in all, another excellent training course which was immensely informative and enjoyable. Whilst realising that a two-day medical training course does not a doctor make, we both felt that should a medical emergency arise, we’d have at our disposal the skills we’d need to make a difference. And if that difference is one between life and death, it seems to me that these are skills well worth having.